Influences: Suzanne Vega reinvents Rumi [rumination]

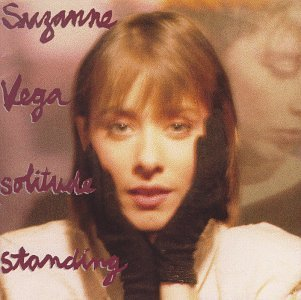

I was pleasantly surprised to note Suzanne Vega has written an op-ed piece in the New York Times today ("The Ballad of Henry Timrod"). My initial introduction to Vega's songwriting happened to come from her participation in Philip Glass's memorable art-song-cycle, Songs From Liquid Days (1986). Around the same time, Vega's own first albums -- the eponymous Suzanne Vega (1985) and Solitude Standing (1987) introduced my ears more fully to her work and likeable voice. I suppose it was in 1985 that I interviewed Glass in San Francisco. (In 1987 or '88, I also interviewed him in New York.) I recall discussing the Liquid Days album with him, and his noting the recent exposure of Vega to a wider audience (though he had known her work for some time in New York).

I was pleasantly surprised to note Suzanne Vega has written an op-ed piece in the New York Times today ("The Ballad of Henry Timrod"). My initial introduction to Vega's songwriting happened to come from her participation in Philip Glass's memorable art-song-cycle, Songs From Liquid Days (1986). Around the same time, Vega's own first albums -- the eponymous Suzanne Vega (1985) and Solitude Standing (1987) introduced my ears more fully to her work and likeable voice. I suppose it was in 1985 that I interviewed Glass in San Francisco. (In 1987 or '88, I also interviewed him in New York.) I recall discussing the Liquid Days album with him, and his noting the recent exposure of Vega to a wider audience (though he had known her work for some time in New York).Anyway, this op-ed piece concerns the little plagiarism allegation or contretemps washing around Bob Dylan at the moment. Vega's opening two paragraphs sets the tone for what's to unfold. She writes,

I AM passionate about Bob Dylan. As a songwriter, I find there is nothing like singing “It’s Alright Ma (I’m Only Bleeding).” It is nearly eight minutes of cascading images, rich language and the coolest, most unexpected metaphors. My synapses light up in little fireworks, making connections they don’t get to make in ordinary life.Now I do not propose, here, to ruminate on Dylan's appropriation (as it's claimed -- I've not reviewed the situation in detail). What interests me involves Coleman Barks and Rumi and Suzanne Vega. Vega introduces this more or less as an illustrative aside. But the aside seemed to me actually more interesting than her main topic. I have not even read to the end of her op-ed piece (I merely have a premonition how things may fare for Dylan). Of course I'll finish reading her piece. But I should not wish the chance to pass to delineate the curious thought that has come to mind from her aside. So: she goes on to write,

So I read with curiosity about the similarities between some lyrics on his new album and the verses of a forgotten Civil War-era poet. Who is Henry Timrod? Is it true that Mr. Dylan has been borrowing from his poetry? I ran out and bought the CD — not downloading it, because I wanted the lyric booklet. I wanted to see the evidence. And, of course, I discovered that he includes no lyrics in the CD package. No words at all, not even liner notes. Bob isn’t making this easy.

It’s modern to use history as a kind of closet in which we can rummage around, pull influences from different eras, and make them into collages or pastiches. People are doing this with music all the time. I hear it in, say, Christina Aguilera’s new album, or in the music of Sufjan Stevens.Or not. Back, rather, first, to Rumi and Barks.

So I had an open mind when approaching this Dylan album -- which is called “Modern Times,” by the way. Does this method of working extend to a lyric? To a metaphor? To Bob Dylan’s taking an exact phrase from some guy we never heard of from the middle of the 19th century without crediting him? That’s what I needed to satisfy myself about.

For example, recently I saw a poem on the subway that startled me. It is by the 13th-century Sufi poet Rumi.

One of my own songs says:

I’d like to meet you

In a timeless, placeless place

Somewhere out of context

And beyond all consequences

I won’t use words again

They don’t mean what I meant

They don’t say what I said

They’re just the crust of the meaning

With realms underneath

Never touched

Never stirred

Never even moved through.

Rumi’s poem says:

Out beyond ideas of wrongdoing and rightdoing,

There is a field. I’ll meet you there.

When the soul lies down in that grass, the world is too full to talk about.

Ideas, language, even the phrase each other

Doesn’t make any sense.

(Jelaluddin Rumi, 1207-1273. Translated from the Persian by Coleman Barks and John Moyne, from “The Essential Rumi,” published by HarperCollins. Copyright ©1995 by Coleman Barks. Reprinted with the permission of Coleman Barks. M.T.A. New York City Transit in cooperation with the Poetry Society of America. Poetry in Motion® is a registered trademark of M.T.A. New York City Transit and the Poetry Society of America.)

Sorry for that chunk of text right there, but I want to make sure everyone is credited properly.

So, I sat on the subway staring at the words, wondering -- how did that happen? I had never even heard of Rumi, and I thought the resonance of ideas was a remarkable coincidence. I felt vaguely guilty and wondered if I should be paying royalties to someone.

But back to Bob Dylan. . . .

What Vega apparently did not particularly consider is that the influence in this case may conceivably -- indeed may well -- have washed the other direction. Rumi may have been influenced by Suzanne Vega's poem (not vice versa). How? Well, let me amend that. Rumi's translator may have put in Rumi's mouth words whose inflection were in some measure influenced by sources such as her own song; so that when -- years later, riding on a New York subway -- she saw those words attributed (correctly enough, as far as that goes) to this 13th century Persian source, she was nonetheless seeing, down-river, a rippling echo of her own songwriting.

Vega's lyrics are from a song entitled "Language," from the above-mentioned 1987 album (Solitude Standing). The interesting thought is that the translator's style and use of language is perchance as influenced as much by his familiarity with American poetic discourse (including the songwriting tradition to which Vega belongs) as it is by the idioms and tropes of 14th century Persian.

Okay: I was gearing up (I thought) to point to Barks' poem being published later than Vega's album. And indeed she cites The Essential Rumi (1995). That was the first book of Barks' Rumi versions finally (after Barks toiled away for the better part of two decades, self-publishing his little volumes) -- finally picked up by a big, established publisher and distributed widely.

However, not so fast. Google research has (somewhat) nipped my notion in the bud. In point of fact, the poem Vega quotes -- later appearing in the source she notes -- evidently first appeared in an earlier, thin volume (Barks' collaboration with scholar John Moyne) published in 1985 (as noted here -- on, of all things, the Out Beyond Ideas dot org website).

Ah well, this remains: ideas and language wash every which way. Even if in the instance, Barks was perchance not (unconsciously) borrowing from Vega, he easily could've been.

Stranger things, Horatio. Actually, what Vega didn't mention (and likely was unaware of) is that her line "In a timeless, placeless place" is even more directly reminiscent of Rumi's poetry than is the poem she saw on the subway. "Placeless place" is a phrase frequently found in Rumi. Though it's akin to the phrase "pathless path" found in some Zen sources perhaps more directly familiar to Vega. But with "placeless place" she seems to have reinvented the Rumi wheel verbatim.

Now I'll read the rest of Suzanne's editorial . . .

where, in end, she takes an unexpected turn.

============

Speaking of Philip Glass: it bears mention that his new choral work, The Passion of Ramakrishna saw its world premiere in Costa Mesa, California yesterday.

Speaking of Philip Glass: it bears mention that his new choral work, The Passion of Ramakrishna saw its world premiere in Costa Mesa, California yesterday.A co-commission by Orange County's Pacific Symphony and the Nashville Symphony, the work will be played in Nashville next February.

The concert yesterday featured special guest violinist Midori -- such a sweetheart she is.

I enjoyed a radio interview with her on NPR (in the past year or so), where I learned of her dedication to new music along with the standard classical repertoire. Among maturing prodigies, she seems to be on a special path. Glancing at her website, look at this sign of good things afoot:

I enjoyed a radio interview with her on NPR (in the past year or so), where I learned of her dedication to new music along with the standard classical repertoire. Among maturing prodigies, she seems to be on a special path. Glancing at her website, look at this sign of good things afoot: As part of its new International Community Engagement Program, Midori's MUSIC SHARING project will visit schools, hospitals, and other institutions in Vietnam in December 2006.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home