1)

The name of Lord Raam's a Unit

our power to say is Zero

put One before Zero Ten it!

else Zero will stay mere Zero!2)

Lord Raam is the Lord of monkeys

he sits 'neath the tree they branch-sit

he treats them as darling flunkies

who's heard of a Lord so compassionate?3)

When green all the kine come grazing

with fruit many folk come dining

when dry people use for kindling

Raam comes to you for refining[the intended sense seems to be: any plant or tree is used by beings and persons as suits their passing needs; whatever they can get from it, they'll get. Similarly, all beings come to us to satisfy their selfish desires. Only Raam comes to us purely for the sake of our own benefit, not to help himself. In this respect, he differs. But then, the devotee may understand that all aspects of his experience -- the promise of the leaf, the fulfillment of the fruit, the desolation and burning of the weary branch -- all of these embody experimental phases of an underlying process of refinement that Raam performs for the soul's ultimate perfection.]

4)

When sun is afar shade deepens

when sun is on high it's absent

Illusion expands when distant

from Raam When he's near it's tacitshade: i.e., the shadow of the person.

[One notes that ideas and figures of speech found in several of Tulsidas's dohas -- including this one, as well as the first verse at top (the mathematical conceit) -- are elaborated and expanded on by Meher Baba in discourses such as those found in

The Everything and the Nothing (1963.)

We know Meher Bwba spent seven years under the guidance of Sadguru Upasni Maharaj, early on. Encountering these specific, familiar poetic / philosophical / metaphysical tropes in Tulsidas's dohas, I couldn't help but passingly wonder whether perchance Upasni might not have had the habit of reciting verses from Tulsidas and Kabir -- although perhaps ultimately the common stock of available metaphors and similies in Indian spiritual lore is pervasive enough as to obviate any certainty of pointing to s specific a source. Still, I wonder.]

5)

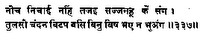

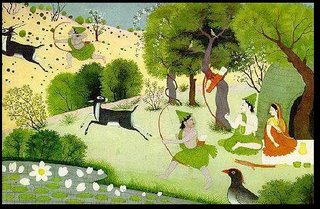

Lord Raam wore bark-clothes in exile

ate forest-fruits grass his bolster

gave Lanka to King Vibheeshan

each action reveals his naturegrass his bolster: that is, he slept on the ground. The scene when Raam, Lakshman and Sita all don clothes made from bark or leaves (at the beginning of their exile), is perhaps among the most heart-rending in the Ramayana.

about

Vibhishan (Wikipedia)

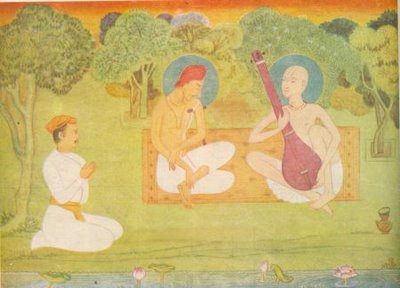

[Jatayu with Raam and Sita at the Panchevati Hermitage, in peaceful times. The illustration is an example of Kangra painting.]

6)

Times gone many died folks die now

and myriad shall croak mañana!

what death was like kind Jatayu's?

he perished protecting Sitatimes gone: in the past

mañana (Spanish): tomorrow

about

Jatayu (Wikipedia). Among ideas Tulsidas refined in his reconception of the

Ramayana, was his idealisation of several figures in the drama (including Lakshman, Jatayu, Hanuman, Vibhishan) as archetypes of attitudes and behaviors devotees may admire and emulate. In several dohas, he boils these principles down to sharp pictures -- such as this, pointing to Jatayu's suicidal and chivalrous self-sacrifice in the cause of seeking to protect Sita, the consort of his friend and Lord Raam (against the abduction perpetrated by Raam's nemesis, Ravan).

7)

The Goddess of Expectation

is quite an ironic marvel!

who serve her gain lamentation

who spurn her grow free of trouble8)

The savvy the brave the noble

the poet and others gentle --

who hasn't been proved ignoble

by greed? Mr. detrimental9)

There's kama and krodh and kanchan

three enemies dark and busy!

the pious and thoughtful person

because of these grows so dizzy!kama, krodha, kanchana (Skt.): lust, greed and anger

10)

A horrible snake that zigzags

black skin and its tongue quick-flutters

will show itself meek and docile

if hearing soft speech that flatters11)

The thing we admire seems sacred

if useless it seems a bum deal

a tooth in the mouth is pearlèd

it falls on the ground? it's bonemeal!12)

Abiding with gentlepersons

the callous remains a villain

a snake in the sandal forest

is nonetheless filled with poison[The above is the preferred version I arrived at after editing. My initial version -- which perchance follows more closely the sequence of thought in the original? -- is seen here for comparison:

A badguy is mean though dwelling

in company with sweet persons

a snake in the sandal forest

is nonetheless filled with poisons ]

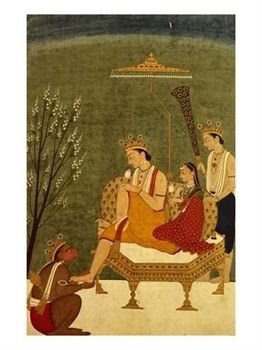

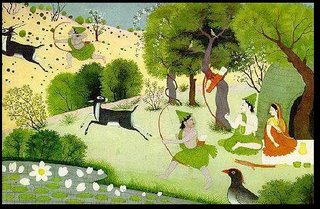

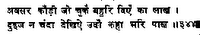

[Raam chasing the magic deer]

13)

A noble whose death is noble

a villain who dies still vile --

Jatayu the first case symbols

Marich shows the second styleabout

Maricha (Wikipedia). When Raam's arrow felled the deer (deceptive transformation-form assumbed by Ravan's magician-counselor Marich), this spelled the death noted by Tulsidas. But by then, he had done his damage: having lured Raam away, so that Ravan could perpetrate his machinations on the hapless Sita. Thus Jatayu (striving to protect Sita) and Marich (a party to her peril) typify in the circumstances of their deaths the symbolism or intention embodied in their deeds while living.

14)

If wary to spend one penny

when facing the hour of need

a billion of later money

will fail to redress that deed[Again, the above is a revised and favored version. My grapples with the verse also included this attempt:

If failing to give one penny

when scarcity's need is present

a billion of later money

will scarcely redeem that moment

However, the version with "need" and "deed" is deficient in terms of prosody (the 2nd and 4th lines lack a final syllable, thus failing the strict form established in the rest of the verses in this sequence). I may yet need to work on this one some more.]

15)

In love's test stone's first sand's second

and water comes last (inscribe them --

stone's line stays sand's lingers water's

is gone) in hate's test reverse them[In this epigram, the poet notes how a line etched in stone will last forever, one drawn in sand will linger but disappear after a time, while one written on water will proverbially vanish at once. This range, he suggests, is applicable to degrees of durability or evanescence in love -- with the permanance of stone representing the ideal condition of love's enduring dedication and continuity. In the case of hatred, he suggests one should adopt an opposite standard: where the ideal, with regard to a condition of aversion or animousity, is to forget it at once (as with writing on water), rather than holding onto the experience. It seems the appeal of the pleasantry lies partly in the poem's extreme concision (its broad principles deftly limned in so telegraphic a fashion), and partly in its little surprise (almost a conceit) of moral symmetry (where the opposite emotions call for inverted scales of value). Even though I failed to pull this verse into a proper doha rhyme-scheme [ABAB], I'm still happy at having at least delineated the poem's sequence of ideas while adhering (though a bit choppily) to the requisite, clipped cadence.]

16)

A guy stubs his toe on stone ouch!

can't punish the stone! shreds pillows

at home In this Age such flourish

they threaten outside their fellowsthis Age: more particularly, Tulsidas references the

Kali Yuga (a thing he was wont to do, indeed a veritable theme in his work.) [The poet notes that in this Age, such irrational and negative behavior is not confined to the home and its pillows; rather, it is converted into many a hazard to society and the world at large. The man stubbing his toe and destroying pillows offers an instructive figure for the absurd phenomenon -- and for a behavioral pattern whose consequences can be noted in our daily newspapers.]

=========

source of Tulsidas verses -- including very literal prose translations done by Dhananjay Kadwane (to whom, thanks). Those served as my basis for re-rendering into these more formal English verses. [Regrettably I cannot read the olden Hindustani nor the modern Hindi. Hopefully I have attached the correct

Devanāgarī graphics to the respective verses above.]