Further google-notes on the Vichitra Vina.

The Nad Sadhana [Jaipur, Rajasthan-based] site includes

these notes:

In general appearance and structure, the vichitra veena is very similar to the northern bin or veena. For an instrument so young, it is fairly widespread. The main difference between the northern veena and the vichitra veena is that the former is a fretted instrument with a bamboo stem while the vichitra veena has a much broader and stronger wooden stem without frets which can accommodate the large number of main and sympathetic strings. This hollow stem, about three feet long and about six inches wide, with a flattop and a rounded bottom, is placed on two large gourds about a foot and a half in diameter. An ivory bridge covering the entire width of the stem is placed at one end. Six main strings made of brass and steel run the whole length of the stem and are fastened to wooden pegs fixed to the other end.

The vichitra veena has about twelve sympathetic strings of varying lengths which run parallel to and under the main strings. They are usually tuned to reproduce the scale of the raga which is being played.

The vichitra veena is played by means of wire plectums (mizrabs) worn on the fingers of the right hand which pluck the strings near the bridge. The notes are stopped with a piece of rounded glass, rather like a paper weight. The musician slides the glass piece from one note to another over the strings by holding it in his left hand. It is rather difficult to play fast passages on the vichitra veena but slow passages emerge on this instrument with a beauty and richness of tone which few other instruments possess.

The obvious disadvantage of this instrument is that a paper weight can never do what human fingers can. And so, some of the delicate graces and embellishments in very fast passages have to be sacrificed. The vichitra veena has these advantages in common with the gottuvadyam of the south.

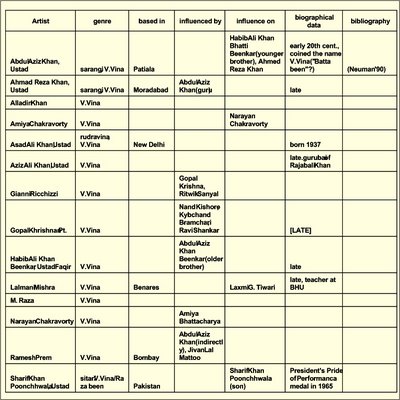

It is said that the Vichitra veena was introduced by the late Ustad Abdul Aziz Khan who was a court musician at Indore. In fashioning the instrument, Ustad Abdul Aziz Khan, during his musical contacts with the south, probably took his ideas from the southern gottuvadyam which was already popular.

Mustafa Raza's

vichitravina.com site may also be noted. He is said to play "khayal gayaki style." His father was Ustad Ahmed Raza (who was a student of Ustad Abdul Aziz Khan). Some interesting remarks about the instrument found there include:

Vichiter Veena's ancient name is Shiv Veena. It is also known previously in different names -- Shutri Veena, Tantra Veena, Batta Veena etc. But today it is known as Vichiter Veena. Ustad Abdul Aziz Khan of Patiala family has given a new life to this instrument. Vichiter Veena is believed to be a divine instrument and the music produced through it always devoted to the absolute. The Veena has the distinction of being the only plucked instrument that is considered to be the purest musical sound and by legend is the foundation of all art.

The Vichiter Veena has four main strings three front side supporting strings and along with two chikaris, 15th Tarabs (resonance strings) having a range of three and half octaves. Resonance strings confine a player to "pure" or "perfect" note as they themselves are tuned on "perfect"....

Dr. Raza is also amusingly quoted in one press clipping: "You can learn the sitar in a year or two, you make more money with it too so why should any one spend six years learning the Vichitra Veena?"

/ / / / /

The

Sadarang Archive website says it is dedicated to "Safeguarding the classical music traditions of Pakistan."

Lakshmi Tewari's website includes a nicely detailed

bio-note about the late vichitra vinakar, Lalmani Misra (1924-1979). Leaving aside here his interesting childhood, this portion has many points of note:

From 1944, he began to be influenced by the Batta Bin of Ustad Abdul Aziz Khan of Patiala. Around 1946, he came to the realization that the Veena is primarily a Hindu devotional instrument. The responsibility of preserving its tradition lay primarily with Hindu artists. If the Hindu tradition that had survived due to the efforts of Muslim musicians now disappeared, the responsibility for its demise would lie with Hindu artists. Therefore, he learned to play Veena in the traditional manner from Abdul Aziz Khan and began his practice in secret.

In 1950, on the invitation of Dr. Ratanjankar to the Bhatkhande Jayanti in Lakhnau’s Morris College, he performed on the Vichitra Veena for the first time. Encouraged by the response of the artists and connoisseurs in the audience, he made the Vichitra Veena his primary instrument.

In 1946, Lalmani Misra established the Kanpur Orchestral Society, and created many compositions. He composed music for plays, as well as directed several of them. In 1947, together with close associates he founded the Bharatiya Sangeet Parishad in Kanpur; under its auspices the Gandhi Sangeet Mahavidyalaya was established on August 16, 1947. He resigned from Kanyakubja College to dedicate his full attention to the new institution.

In 1951, the world renowned dance maestro Uday Shankar appointed him the music director of his troupe. Lalmani Misra was just 27. In 1951 and 1954, with Uday Shankar’s troupe, he toured countries like Sri Lanka, England, France, Belgium, America, and Canada, to very favorable reviews of his music direction and Veena concerts. A Hollywood film company invited him to help make an Indian film. Not used to the atmosphere in the West, he turned the offer down. After returning to India, he was asked to compose music for Hindi films. But his interest in music scholarship and teaching pulled him back to Kanpur. In the course of his world travels, he came to realize that musicians require higher education as well. He went on to receive a Sahitya Ratna, an M.A. from Agra University, and a Ph.D. from Kashi Hindu Vishwavidyalaya.

In 1955, in his capacity as the first Registrar of the Akhil Bharatiya Vandharva Mahavidyalaya Mandal, he organized the work of the institution. But the growing demands of the job took him away from his music practice, and he gave up his duties at the Mandal. At the urging of friends, he became Principal of Gandhi Sangeet Mahavidyalaya in 1957. Sangeet Martand Omkarnath Thakur wanted him to join the Music Department at Kashi Hindu Vishwavidyalaya. After much persuasion, he agreed to leave Kanpur for Varanasi, and joined the Instrumental Department as Reader in 1958, believing that it was not the title but the work that brought greatness to an artist.

He made many major advances in the field of music instruction at Kashi Hindu Vishwavidyalaya. After intense effort, he created a Veena on which all the exercises in Bharat’s Sarana Chatushtadi could be played, and the 22 shrutis recorded by Bharat could be heard and played. After hearing these shrutis on his Veena, Indian and Western scholars alike praised his achievement.

He studied both academically and empirically Indian instruments of the ancient, medieval, and modern eras, and proved that Amir Khusro had nothing to do with the evolution of the Sitar and the Tabla. The sitar evolved naturally from the ancient Tritantriya Veena, and Tabla from the Pushkar Vadya. The modern Sarod and medieval Sursingar and Rabab are evolved forms of the ancient Chitra Veena. His research findings in the field of music created a sensation, and debunked many commonly accepted myths.

Lalmani Misra helped create and reform the syllabi of prominent educational institutions and universities. Having created many instruments, he demonstrated them to the public. After the publication of material for smaller classes, he started work on books on Vedic music and the Sitar, but could not complete them due to poor health.

Lalmani Misra is one of those seminal artists of the music world who excelled as a performer, critic, and scholar. According to him, India has two types of scholars: academic and empirical. The empirical scholar is the one that tests ancient principles on the platform of contemporary music, and puts his faith in its growth and evolution. On the other hand, the academic scholar worships tradition at the cost of new currents in art, and wants the artist to retreat in the past rather than look forward.

Lalmani Misra was working on specific research, such as Vedic music, the rebirth of dhruvapad-dhamar, and the promotion of instrumental music, when he suddenly took ill. At the age of 55, on July 17, 1979, he left the music world and ended his tenure on earth prematurely.

My question include: what is that Batta Vina of Abdul Aziz Khan? And what is this about Lalmani Misra "creat[ing] a Veena on which all the exercises in Bharat’s Sarana Chatushtadi could be played, and the 22 shrutis recorded by Bharat could be heard and played"? Does this suggest that he MODIFIED the Vichitra Vina? If that's the meaning, then one should wish to know about those who may build instruments on his model.

/ / / / /

Lalmani Misra's son

Gopal Sankar Misra also played vichitra vina (and recorded one LP with Real World records in UK -- I've not yet heard it); he passed away in 1999. His sister,

Ragini Trivedi (of Indore), plays sitar. (She could be a good source for info about her father's vina.)

More about Ragini Trivedi: here's her very interestingly written

review of a sitar album (viz., Chandrakant Sardeshmukh's

Pure Joy [

Darshanam, 1998]).

Another, longer article of Ragini Trivedi's: "

If Music be the Soul...." (from ArtScape) -- she writes knowledgeably and interestingly.

Ragini's interestingly appreciative yet critically equivocal review of Shahid Parvez's performance (at a music festival in Indore in 1999) is worth quoting:

The second half of the evening carried the audience into realm of further abstraction. Shahid Parvez, on the verge of being a legend, revealed all on his magical Sitar. Bageshri was the vehicle for demonstration of his skill, this evening. During the Alaap itself, he fascinated one and all with his Meend work. Enticing and amazing, while it succeeded in riveting the attention of the audience, the deft display did little to maintain the mood of the Raga. The slow and rapid compositions were both in Teen Taal and the medium paced composition was in Ek Taal. He brought the evening to a reluctant close with a rendering of a Bhairavi Gat composed in Addha Taal. Even though the compositions were different, the style could easily be discerned as that of his mentor and uncle, Ustaad Vilayat Khan. With a perfect accompaniment on Tabla by Mukesh Jadhav, Shahid could well involve the audience and transport them; he could also break the charm and make them evaluate his effortless mastery over the instrument without any undue influence. Such a practice might bode ill for ancient aesthetics, but it certainly goes a long way in garnering support for Indian Classical Music in its own fashion.

-- from her

review in ArtScape.

Indore is the largest city in Madhya Pradesh (186 km from Bhopal -- due west, looks like).

Note: This is one of the very best listings of professional musicians' contact info in India -- Art India Net. Astonishingly good in fact./ / / / /

Note: there's a

Pt. Lalmani Misra Music Festival held annually in Bhopal, in August, organized by

Madhukali (the organization named after a raaga created by Lalmani Misra).

Also note (per Wikipedia

bio for Allauddin Khan): the Bhopal-based, state [Madhya Pradesh]-run Allauddin Khan Sangeet Academy has an annual festival, in Maihar, in February or early March. (Allauddin Khan had been court musician for Maihar maharajas.)

Distance between Bhopal and Maihar: 359 km.

/ / / / /

I've seen two or three websites that offer vichitra vinas for sale.

Offhand,

this is the only one where the photos impress me -- as presenting a nice-looking instrument. (Some I've seen seem to overdue the inlaid ivory. This has some, but not excessive.) The company in fact is based in Germany; they import their instruments from various manufacturers; so one doesn't (from this site) know who the builders are. The price however (1290 EUR = $1645) is also lower than other vichitra vinas I've seen online.

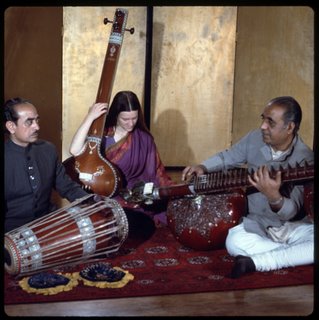

The Ali Akbar College of Music offers

a vichitra vina (for $3,000), noting it's built by Mangla Prasad Sharma. Their

guarantee is worth noting (as is likewise a similar one from the German folks at Tarana).

Another purveyor (are they actually builders?) of vichitra vinas is the new outfit called

Madhubani (in Delhi).

Also note the

Bina Musical Stores website (Delhi-based).

/ / / / /

This article (in The Hindu, by Leela Venkataraman) reports on a conference in Delhi regarding the culture of instrument-making, and mentions the Calcutta instrument-builder Murari Mohan Adhikari as having "fashioned "over 100" Rudra vinas -- "which starts with an elaborate prelude of ritual and prayer before selecting the right wood, seasoning it and then sizing and fashioning it to the exact torso and neck measurements of the individual musician!" The article also amusingly quotes the late Gopal Krishan, regarding his practice of vichitra vina: "When I settled down in the Padmasana, with the baby I was asked to look after ('or else no food,' was the threat held out) on my lap, and practiced for hours, the little one just slept through."

The article also mentions (and critiques) a newer instrument:

For the today's musician, in Damascus today, in New York a couple of days later, travelling with large instruments with two resonators like the veena can be a nightmare. Vainika Suma Sudhindra of Karnataka has invented a new instrument named Tarangini — one that is compact, light, weather resistant and travels well. Sruti stability, ensured by guitar keys, does away with the pegs of the veena. The acoustic resonator of the conventional veena is replaced by a magnetic pickup and the hind resonator made of fibreglass can be unscrewed and packed away separately! But its music sounds more like the electric guitar. Some instruments, it would seem, will not be easily substituted.

Yet another interesting point made is this:

Teak forests are no longer plentiful and other types of wood have to be used for making musical instruments. Raw material like bone and ivory are no longer easily available and substitutes are being experimented with. Ravi Kiran, the chitra veena expert recounting his experience with the instrument, said that after trying out many metals for the slide bar called gottu used to glide on the strings, he now uses a Teflon side bar, which is smooth and easy to wield.

The article concludes with this anecdotal flourish:

Gopal Krishnan [sic; Krishan], the vichitra veena maestro, was jailed during the British Raj. He mesmerised the hardened criminals in his cell with music played on ektara, the only instrument he was allowed to take with him. He played it like a veena and his live demonstration during the symposium floored all with its undiluted sweetness.

/ / / / /

A certain

Concise Dictionary of Hindustani Music, by Ashok Da Ranade (2006), lists a section on the Batta Been.

Ah!

here is why it is called the Batta Been! (and note, too, the important point about variations in numbers of strings) --

The vichitra veena has nine to eleven main strings and eleven to fifteen sympathetic strings. The number of strings (main as well as sympathetic), their tuning system and their gauge vary from artist to artist.

The vichitra veena is played with the help of a small egg- shaped glass, called batta, which looks like a paper weight (although it is bigger than a paper weight), held in the left hand and made to slide upon the strings. In the right hand, the artist wears sitar-like plectrums on the index and middle fingers. Some artists wear a small plectrum on the small finger as well to facilitate playing the drone strings.

The author then follows that up with an interesting but mildly absurd remark --

Because of various reasons the instrument is now losing its popularity among the younger generation of artists. The introduction of the slide guitar, a popular western instrument, to Hindustani classical music is one of the principal reasons for its decline.

(Evidently these notes, generally good, are drawn from a certain Suneera Kasliwal,

Classical Musical Instruments, Delhi (2001))

/ / / / /

Curiously, the flowery prose in the opening paragraph of an essay (

Nestling Among Honey-Buds) by Dr. Rajiv Trivedi [presumably related to Ragini Trivedi?] hints at vichitra vina conceived not as modern invention, but as a revived ancient instrument:

If it was Rosebud that haunted Citizen Kane all his life, it was nectar of honey-buds, which sweetened the notes of that ancient instrument, whenever the maestro caressed it. Vedic Bana, called Brahmaveena, Ghoshvati or Ektantri Veena in ninth century AD is known today as Vichitra Veena. When one comes to learn that Madhukali [sliver of honey?] is an organisation dedicated to the memory of internationally renowned Vichitra-veena player Sangeetendu Dr. Lalmani Misra, he ceases to wonder why such great masters as Pt. Ravishankar, Pt. Hariprasad Chourasia, Pt. Shivkumar Sharma, Ustad Zia Fariddudin Dagar, Dr. N. Rajam, Pt. Rajan & Sajan Mishra have accorded their patronage and unreserved support to it. Named after one of the Raga-s this avid scholar created, Madhukali is also the name of the choral group that in the past fifteen years has established the joy and power of group-singing. Madhukali Vrind performed with probably the largest group ever, which included almost 5,000 children in 1986. By picking up choicest poetry of traditional and modern poets, Madhukali Vrind has created awareness in the young generation for the form of Vrindagana, as well as good poetry throughout Madhya Pradesh.